Efficient compression of congruence class automations

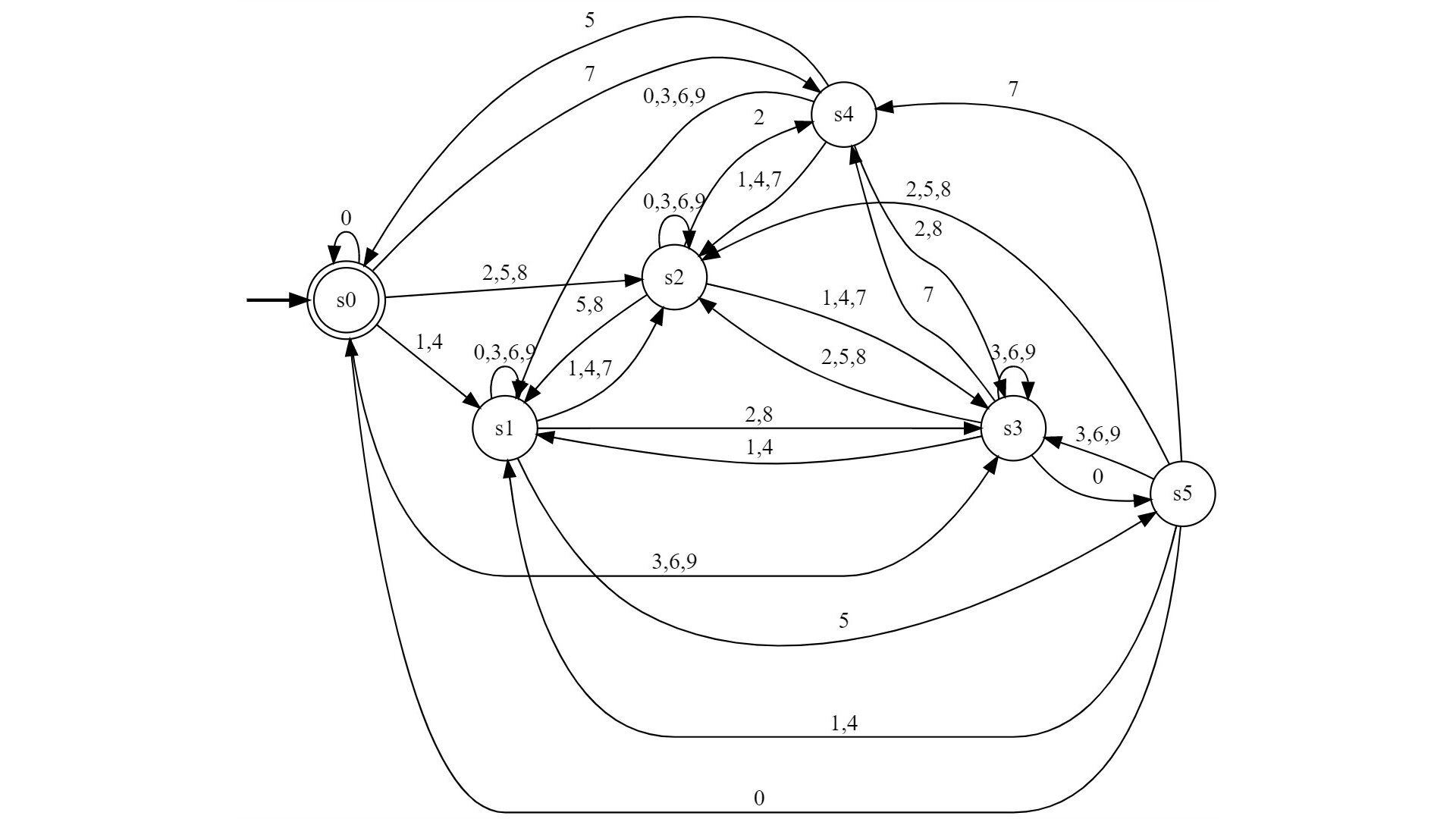

As already discussed in the previous post, any radix-b number with can be accepted by finite automata in a digit-by-digit manner. However, the construction is not always optimal. The amount of states required is not always the amount of congruence classes. In this post we will examine when exactly the finite automata can be simplified by combining states. Reducing the amount of states will also help produce a much simpler regular expression, for example, with the Kleene construction.

General way to optimize an automation

Of course, we can optimize the DFA with the well-known algorithm based on the Myhill-Nerode theorem. Unfortunately, even an optimized implementation is not efficient enough to do the optimization for large and , because the complexity of the algorithm expressed in these terms is , as the algorithm needs to iterate over all pairs of states and consider all the outgoing transitions ( in each state). With this tool we can run the algorithm and get the following results for and :

m= 1 |Z|= 1 Z = [[0]]

m= 2 |Z|= 2 Z = [[0], [1]]

m= 3 |Z|= 3 Z = [[0], [1], [2]]

m= 4 |Z|= 3 Z = [[0], [3, 1], [2]]

m= 5 |Z|= 2 Z = [[0], [2, 1, 3, 4]]

m= 6 |Z|= 4 Z = [[0], [4, 1], [5, 2], [3]]

m= 7 |Z|= 7 Z = [[0], [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]

m= 8 |Z|= 5 Z = [[0], [5, 1], [6, 2], [7, 3], [4]]

m= 9 |Z|= 9 Z = [[0], [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]]

m=10 |Z|= 2 Z = [[0], [5, 4, 3, 2, 7, 6, 9, 8, 1]]

m=11 |Z|=11 Z = [[0], [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]

m=12 |Z|= 7 Z = [[0], [7, 1], [8, 2], [9, 3], [10, 4], [11, 5], [6]]

m=13 |Z|=13 Z = [[0], [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]

m=14 |Z|= 8 Z = [[0], [8, 1], [9, 2], [10, 3], [11, 4], [12, 5], [13, 6], [7]]

m=15 |Z|= 4 Z = [[0], [13, 10, 7, 4, 1], [5, 2, 8, 11, 14], [9, 6, 12, 3]]

m=16 |Z|= 9 Z = [[0], [9, 1], [10, 2], [11, 3], [12, 4], [13, 5], [14, 6], [15, 7], [8]]

m=17 |Z|=17 Z = [[0], [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]

m=18 |Z|=10 Z = [[0], [10, 1], [11, 2], [12, 3], [13, 4], [14, 5], [15, 6], [16, 7], [17, 8], [9]]

m=19 |Z|=19 Z = [[0], [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]]

m=20 |Z|= 3 Z = [[0], [13, 11, 15, 17, 5, 3, 7, 9, 19, 1], [12, 10, 14, 16, 4, 2, 6, 8, 18]]

Here, is the set of states in the new, minimal DFA. is a set of equivalence classes that represent which states can be combined into one state. These equivalence classes have been computed for . That is why, for example, for states 0 and 4 aren’t in one equivalence class. They can’t be equivalent, because state 4 is intermediate while state 0 is final.

Computing equivalence classes ahead-of-time

As you can see, there is clearly a pattern in the equivalence states above. For example, we can see that no states are equivalent when is prime. By further examining the data above we can even conclude that the DFA probably can’t be simplified if i.e. if and are coprime.

After formally examining when the states can be combined I came up with the following result:

Theorem

If and , then the minimum finite automation can be constructed as follows:

where is the set of equivalence classes of the following equivalence relation:

Proof

By definition of , we know that:

Because , it follows that the mapping is surjective. In other words, implies that every state has at least one transition to any other state. Any change to this mapping will shift it. As , any shifted mapping will lead to at least 1 digit such that and .

Thus, 2 states are equivalent if and only if they have equivalent mappings which is equivalent to:

First corollary

It follows, that if , and , then no states can be combined and the minimal automation has states.

Second corollary

If and , then the amount of states (before splitting each equivalence class in final states and non final ones as shown in the theorem) is equal to the following set of orbits:

Example implementation

This Java method uses the results above to compute the equivalence classes efficiently:

public static List<List<Integer>> computeEquivalenceClasses(int b, int m, HashSet<Integer> finalStates) {

assert m <= b;

assert !finalStates.isEmpty();

// Union-Find datastructure, preferrably with union-by-rank and path compression

UnionFind equivalenceClasses = new UnionFind(m);

int bmgcd = Euklidian.gcd(b, m);

if (bmgcd == 1) {

return equivalenceClasses.getDisjointSets();

}

int optimizedM = m / bmgcd;

// loop through every set in the new set of equivalence classes

for (int anchor = 0; anchor < optimizedM; anchor++) {

int current = anchor; // [anchor] is the equivalence class

// oppositeAnchor is the element that is final if anchor is intermediate

// and intermediate if anchor is final

// if oppositeAnchor == anchor, then it is considered as not yet found

int oppositeAnchor = anchor;

boolean anchorFinal = finalStates.contains(anchor);

for (;;) {

current = (current + optimizedM) % m;

if (current == anchor) {

break;

}

boolean currentFinal = finalStates.contains(current);

if (currentFinal == anchorFinal) {

equivalenceClasses.union(current, anchor);

}

else if (oppositeAnchor == anchor) {

// "initialize" oppositeAnchor

oppositeAnchor = current;

}

else {

equivalenceClasses.union(current, oppositeAnchor);

}

}

}

return equivalenceClasses.getDisjointSets();

}

If we use a union-find datastructure with union in (e.g. union-by-rank with path compression), then the complexity of the algorithm is which is much better than .

Case when m > b

In case the equivalence relation depends very much on the set of final states . With the Myhill Nerode theorem we get:

Conclusion

With the above theorem it is easy to implement a much faster algorithm that computes equivalent states. It also gives an intuition, why for example it is harder to test whether a decimal number is divisible by 9 than to test whether a decimal number is divisible by 5, if we measure “hardness” by the amount of states in the minimal DFA. It is the case because and .